- Home

- Species & Infections

- Malassezia

Malassezia - A Skin Fungus You Cannot Overlook

Updated 8/15/2025

Written by Molecular Biologist Dr. Vibhuti Rana, PhD

Out of the many fungal pathogens affecting the human body, the species belonging to the opportunistic Malassezia genus are known for their ability to cause superficial skin infections. Many superficial infections are caused by fungi that target the skin. Some of these are dandruff, atopic dermatitis, eczema, ringworm, athlete’s foot, jock itch, and nail infections (onychomycosis). The fungi which cause these and other skin infections are categorized into two groups: the ascomycete dermatophytes (which include the genera Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton) and basidiomycete fungi in the genus Malassezia (White). Among the various species of Basidiomycetous fungi, Malassezia species and Cryptococcus belong to the pathogenic category of fungi (1). The following article will enlighten you with the specifics of pathogenesis, causes, and treatments of this Malassezia.

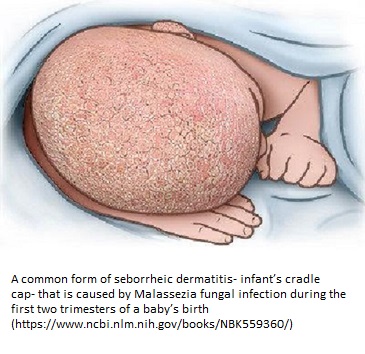

Malassezia affects animals as well as humans, and causes a myriad of chronic, superficial skin infections. Here’s an interesting fact- an infant’s cradle cap (the infantile seborrheic dermatitis flaky patchy scalp of a baby during its first three months) can be attributed to the Malassezia fungal infection! It does not itch, but it can spread to other parts of the baby’s body like eyelids, neck, chin, or the nappy area (2).

Like most of the fungal species, Malassezia lives as a part of normal human microflora under normal circumstances (known as commensalism); it is not able to invade the hosts with a strong immunity. So, when does it attack? As expected, those with a compromised or weakened immune system become the target of Malassezia-mediated fungal infections. It is one of the most commonly present pathogens of the human skin sites and is generally found on warm-blooded animal skin (3).

The species of genus Malassezia cause infections ranging from pityriasis versicolor and Malassezia folliculitis to seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff, and atopic dermatitis to psoriasis. Sometimes, certain individuals may be affected with confluent and reticulated papillomatosis, onychomycosis, and transient acantholytic dermatosis (4). Most of the infections persist for long time and are recurrent in nature. Borda and Wikramanayake, in a review published in 2015 have discussed that the incidence of seborrheic dermatitis ranges up to 80% in patients with HIV (5).

Studies that are trying to build a relationship between commensals and the human skin show that this interaction is brought about by phospholipases and certain signaling molecules in case of dandruff and seborrheic dermatitis, respectively (6). It is also believed that patients who have limited mobility, like those with spinal cord injuries, are likely to get Malassezia infections, specifically seborrheic dermatitis (7).

People diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, and are on immunosuppressants post-transplant surgery, and use broad spectrum-long term antibiotics are also at high risk of developing Malassezia species infections. Malnourishment and corticosteroid therapy (having greater levels of plasma cortisol) are also predisposing factors for developing pityriasis versicolor.

Identification of Malassezia Species

Named after Louis-Charles Malassez in late 19th century, the Malassezia yeasts grow quite slowly in vitro. The isolation and culturing of this species is also cumbersome (8).

It is also known by the synonym of Pityrosporum, a name by which it was previously addressed. Previously, it was thought to consist only of two species- Pityrosporum orbiculare and Pityrosporum ovale.

However, in 1996, seven species were identified using specialized microscopic and ultrastructural morphological assessment. These species were M globosa; M restricta; M obtusa; M slooffiae; M sympodialis; M furfur; and the non-lipid dependent M pachydermatis (8,9).

Lately, Malassezia yeasts have been classified into at least 14 species. Amongst these, eight have been isolated from human skin, including Malassezia furfur, Malassezia pachydermatis, Malassezia sympodialis, Malassezia slooffiae, Malassezia globosa, Malassezia obtusa, Malassezia restricta, Malassezia dermatis, Malassezia japonica, and Malassezia yamatoensis (10).

Most closely, Malassezia resembles plant-infecting Urediniales (rusts) and Ustilaginales (smuts). As far as sexual reproduction is concerned, this species possibly grows sexually after infection on human skin.

Malassezia pachydermatis can grow on routine laboratory media and does not depend upon a lipid source for its growth and seldom affects immunocompetent people. In a collaborative study between Showa University Fujigaoka Hospital, Yokohama, Japan and Parasitology-Mycology Unit, Alfort’s National Veterinary School, France, Nakabayashi et al in 2000 found that overgrowth of M. globosa and M. furfur were common in most of the cases of pityriasis versicolor, seborrheic dermatitis, and atopic dermatitis as compared to normal healthy controls (11,12).

The normal speciation or genetic drug susceptibility testing of these species are quite complicated and cumbersome due to difficulty in their culturing (13, 14). Much more complicated is the understanding of their role and species involvement in blood stream infections. Malassezia species can be generally identified by microscopic techniques. However, this is not at all precise and may cause faulty colony characterization. Therefore, additional biochemical assays like catalase tests, lipid starvation tests (checking growth in absence of lipids), esculin and tryptophan tests are necessary to move a step ahead in identification (12). Nowadays, advanced genomics and phylogenetic analyses are quite helpful in correct identification and classification.

Diseases Caused by Malassezia

Multiple skin-related superficial infections and rarely, systemic infections, occur due to Malassezia species. The main ones-pityriasis versicolor and seborrheic dermatitis occur in immunocompromised patients recurrently in a seasonal pattern (4).

Pityriasis versicolor, considered by many as a cosmetic disorder, is ascribed to transformation of the Malassezia yeast to the mycelial, pathogenic form. It is quite common in tropical regions as the fungus requires high temperature and high humidity to flourish and multiply (15). It commonly affects individuals ranging from 20-40 years and is rarely found in children and elderly. This recurring disease is found as oval shaped infectious lesions mostly seen in the trunk and arms of the human body. The pigmentation of these lesions can be varied- skin, white, pink, brown, etc.

Though both are common dermatological disorders, seborrheic dermatitis is different from dandruff in its form and nature. The latter is presented by flaky and itchy scalp without any directly visible inflammation of the scalp. On the other hand, seborrheic dermatitis is seen not only in the scalp, but also in other sebum rich areas of the body, and is accompanied by inflammation and pruritus – (itchy skin) (5). SD is common during the age periods where sebum glands are most active, i.e., the first couple of months of an infant’s life (infantile seborrheic dermatitis), during puberty, and when sebum excretion is diminished after 50 years of age (16).

Malassezia folliculitis, a form of seborrheic dermatitis is seen in the hair follicles (individual pilosebaceous units) upon infection by Malassezia species, and may be accompanied by other microbial infections including staphylococci and propionibacteria (17).

Atopic Dermatitis, characterized by itching, eczema like scaling, and light-colored pigmentation, can be attributed to Malassezia infections. Adults rarely manifest the symptoms of this disease, while in children, it is quite common. Most of the children outgrow atopic dermatitis when they enter adolescence (18).

Malassezia pachydermatis is the most common pathogen that causes Malassezia dermatitis. The epithelial cells of the skin, when disrupted (cutaneous epithelial barrier broken) provide the best entry point and surface for growth and colonization to the pathogen (19).

How Does Malassezia Infect the Human Body?

As explained before, it is now evident that Malassezia depends upon sebum or lipid rich substrates for its growth and sustenance. These sebum rich areas are mainly scalp, trunk (torso), back, and face. Very rarely, it may also exploit other areas such as genitalia, legs, or arms (8). In 1988, Wilson and Walshe, from the Stoke Mandeville Hospital, Aylesbury, presented this finding after studying 20 patients who suffered from spinal injuries. A common observation in paraplegic patients was that they moved minimally due to their injury and only took bed bath, leading to accumulation of sebum and greasy hair- an environment which is most suitable for the growth of P. ovale species of Malassezia.

Malassezia, like other skin-residing fungal species like Candida albicans, secretes fungal enzymes which promote host invasion and proliferation. However, it cannot produce fatty acids like C. albicans or other fungi. Instead, it exploits its lipases and phospholipases to procure host fatty acids for their growth (3).

Medications like griseofulvin, ethionamide, buspirone, haloperidol, chlorpromazine, IL-2, interferon-α, methyldopa, and psoralens, along with deficiencies of pyridoxine, zinc, niacin and riboflavin may induce SD-like dermatitis symptoms (5).

Antifungals Used for the Treatment of Malassezia

The availability of new tools such as genomic and proteomic analyses has begun to provide a new insight into the pathogenetic mechanisms involved.

While cradle cap is not contagious and does not require any medication in infants, it can be softened and brushed off gradually by applying zinc paste or olive oil.

Other Malassezia infections require different kinds of anti-fungal therapy. Pityriasis versicolor and seborrheic dermatitis can be treated using topical drugs like propylene glycol, ketoconazole or zinc pyrithione shampoo, ciclopirox, and selenium sulfide. In some cases that appear tricky, fluconazole or itraconazole can also be used (15).

These infections are generally recurring, so we need to choose the drugs which lengthen the period between each episode of infection. Owing to their superficial, but recurring nature, with an added risk of developing systemic infections of the blood, it is important to formulate and develop highly sensitive and robust techniques for their isolation, culturing, species identification, and drug susceptibility testing (Pedrosa).

Availability of genomic (gene-pool associated) and proteomic (protein-pool at a given time) tools may also provide a new insight into the pathogenic mechanisms involved.

About the Author

Dr. Vibhuti Rana completed her Bachelors's Degree (Bioinformatics Hons.) from Punjab University and accomplished her Master’s Degree (2012) in Genomics with a Gold Medal from Madurai Kamaraj University, India. In 2020, she received her doctorate in Molecular Biology from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research-Institute of Microbial Technology in affiliation with the Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India.

Her areas of focus include microbial drug resistance, epidemiology, and protein-protein interactions in infectious diseases. As a Molecular Biologist with extensive experience with infectious diseases, we are happy she is part of the YeastInfectionAdvisor team.

Have Any Questions About Malassezia?

Do you have any questions about Malassezia or yeast infections in general? Ask your question here or contact us using the contact page of this website. It is also always a good idea to talk to your doctor as well.

Questions From Other Visitors

Click below to see questions from other visitors to this page...

Can you recommend an effective shampoo other than Nizoral which was ineffective in ending a twice occurring outbreak on my scalp?

I’ve had an itchy scalp for years, even after washing my hair. In the last 1-2 yrs I’ve experienced a generalized itchiness across my face also. I’ve been …

What's a good treatment protocol for Malassezia yeast?

Hello!

Can you please advise on the protocol for Malassezia yeast in the gut? It was confirmed by a colonoscopy biopsy. As I read it feeds on fat …

Is Malassezia contagious?

I have multiple myeloma and my boyfriend has this skin condition. Can he give this to me?

Can dogs pick up Malassezia, from grass or dirt in a yard?

Recently, I and my son, have been diagnosed with Malassazia sympodialis & Malassazia Globasoa, in the scalp.

We lived in a home for 3 years, that had …

How long can a person use 2% ketoconazole shampoo to treat Malassezia on their scalp with hair loss?

I’m 45 and live a natural life, organic and naturopathic so when my hair started falling out and my scalp was tender and itchy, I didn’t think it would …

What is the root cause of Malassezia infections?

What is the root cause then? If it keeps coming back and using topicals and anti-fungals which act as a band aid treatment, what is the CURE?

Question about alopecia and fungal infections?

I've been researching alopecia for a friend who's grandson has had it since 6 months old. I think it has something to do with glyphosate in the family …

How should I treat Yeast Overgrowth in a teenage girl?

My 17 year old daughter has high overgrowth of Candida krusei, Candida glabrata, Aspergillus fumigatus , and mild overgrowth of Candida parapsilosis …

What does a person 78 years old use to kill malassezia on scalp?

Scalp get flakes that stick

How do you treat Malassezia in eyelids, gums around teeth?

I’m a Type 1 Diabetic x 46 years, age 68. I’m on an insulin pump and never thought my diabetes was uncontrolled. Highest Hbg A1C was 8.1 and that was many …

Dr. Rana's Medical Reference

- Saunders CW, Scheynius A, Heitman J. Malassezia fungi are specialized to live on skin and associated with dandruff, eczema, and other skin diseases. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(6):e1002701. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002701. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3380954/

- White TC, Findley K, Dawson TL Jr, et al. Fungi on the skin: dermatophytes and Malassezia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4(8):a019802. Published 2014 Aug 1. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a019802 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4109575/

- Difonzo EM, Faggi E, Bassi A, Campisi E, Arunachalam M, Pini G, Scarfì F, Galeone M. Malassezia skin diseases in humans. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013 Dec;148(6):609-19. PMID: 24442041. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24442041/

- Borda LJ, Wikramanayake TC. Seborrheic Dermatitis and Dandruff: A Comprehensive Review. J Clin Investig Dermatol. 2015;3(2):10.13188/2373-1044.1000019. doi:10.13188/2373-1044.1000019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4852869/

- Hay RJ. Malassezia, dandruff and seborrhoeic dermatitis: an overview. Br J Dermatol. 2011 Oct;165 Suppl 2:2-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10570.x. PMID: 21919896. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21919896/

- Wilson, C. L., & Walshe, M. (1988). (12) Incidence of seborrhoeic dermatitis in spinal injury patients. British Journal of Dermatology, 119(s33), 48–48. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb05386.x

- Gupta AK, Kohli Y, Summerbell RC, Faergemann J. Quantitative culture of Malassezia species from different body sites of individuals with or without dermatoses. Med Mycol. 2001 Jun;39(3):243-51. doi: 10.1080/mmy.39.3.243.251. PMID: 11446527. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11446527/

- Gupta AK, Batra R, Bluhm R, Boekhout T, Dawson TL Jr. Skin diseases associated with Malassezia species. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004 Nov;51(5):785-98. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.12.034. PMID: 15523360. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15523360/

- Prohic A, Jovovic Sadikovic T, Krupalija-Fazlic M, Kuskunovic-Vlahovljak S. Malassezia species in healthy skin and in dermatological conditions. Int J Dermatol. 2016 May;55(5):494-504. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13116. Epub 2015 Dec 29. PMID: 26710919. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26710919/

- Nakabayashi A, Sei Y, Guillot J. Identification of Malassezia species isolated from patients with seborrhoeic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, pityriasis versicolor and normal subjects. Med Mycol. 2000 Oct;38(5):337-41. doi: 10.1080/mmy.38.5.337.341. PMID: 11092380. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11092380/

- Difonzo EM, Faggi E. Skin diseases associated with Malassezia species in humans. Clinical features and diagnostic criteria. Parassitologia. 2008 Jun;50(1-2):69-71. PMID: 18693561. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18693561/

- Pedrosa AF, Lisboa C, Gonçalves Rodrigues A. Malassezia infections: a medical conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Jul;71(1):170-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.12.022. Epub 2014 Feb 22. PMID: 24569116. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24569116/

- Thayikkannu AB, Kindo AJ, Veeraraghavan M. Malassezia-Can it be Ignored?. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60(4):332-339. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.160475. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4533528/

- Faergemann J. Management of seborrheic dermatitis and pityriasis versicolor. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000 Mar-Apr;1(2):75-80. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200001020-00001. PMID: 11702314. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11702314/

- Gaitanis G, Magiatis P, Hantschke M, Bassukas ID, Velegraki A. The Malassezia genus in skin and systemic diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012 Jan; 25(1):106-41. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22232373/

- Leeming JP, Holland KT, Cunliffe WJ. The microbial ecology of pilosebaceous units isolated from human skin. J Gen Microbiol. 1984 Apr;130(4):803-7. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-4-803. PMID: 6234376. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6234376/

- Williams HC. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000 Oct;25(7):522-9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00698.x. PMID: 11122223. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11122223/

- Outerbridge CA. Mycologic disorders of the skin. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract. 2006 Aug;21(3):128-34. doi: 10.1053/j.ctsap.2006.05.005. PMID: 16933479. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16933479/

Home Privacy Policy Copyright Policy Disclosure Policy Doctors Store

Copyright © 2003 - 2025. All Rights Reserved under USC Title 17. Do not copy

content from the pages of this website without our expressed written consent.

To do so is Plagiarism, Not Fair Use, is Illegal, and a violation of the

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998.